Go through music industry’s amazing journey

We love stories of books and movies. We also love music. What about telling the story of the music industry then? Studying history is a key factor of success for upcoming challenges. The industry of music has been going through ups and downs for over 150 years, but we hardly know a thing about it. Get to know it all from the first origins of the music industry to worthy insights about streaming. Incredibly enough, you will see that everything that is changing now was one way or another already written in the past.

Introduction

I wrote and published in French part of this study in early 2014. At that time, all relevant charts (US, UK, France, Germany, Japan, Canada etc.) weren’t taking into account Streaming on their rankings, which was just plain wrong. The idea of the article was to highlight the deep meaning of the music industry to understand how ignoring streaming was a complete nonsense. Ironically, in the months following these articles most charts changed their rules to consider a calculation involving streams rather than only sales.

A couple of years later the picture of the music industry for the future was pretty unclear as many questions were still floating all around:

- is streaming as legitimate as a sale?

- What will happen with physical formats?

- … and with downloads?

- How do current figures compare with past eras’ figures?

- Will artists keep releasing albums or standalone songs only?

- Are compilations going to disappear?

- Will upcoming evolutions benefit or penalize some types of music?

- What does music industry ultimately mean with all these changes?

- How will be its jigsaw by 2020?

In our way of understanding the future, we will start by looking at the past – from way back in the century XIX. Sounds boring? Stop it! Not only you will be getting all answers of previous questions, know what will happen in upcoming years but you will also understand in full everything from the past!

Parts of this article are highlighted in green color during this article. Please focus on them as they are past happenings which explain the meaning of the current context.

The 2018 update puts the streaming world to the test to see how sustainable it is. It’s business model and global impact are detailed as well as how the music industry adjusted itself to it.

Music industry – The past

19th century – The pre-recordings era

What’s the music industry?

This first section, which brings us back during years 1800, is maybe the most important of all. The major idea brought by it resolves a continuous confusion that makes the 2016 universe impossible to understand: the fundamental difference between the Music industry and the Recordings industry.

Since it’s all we ever knew during our lifetime, we tend consider as a given that the industry of recordings is equal to the industry of music, which is deeply wrong.

Three very distinct parts define the music industry, the recording being only one of them:

- the composition, created by the author and / or the composer and owned by the latter.

- the recording, realized by the artist

- the media, produced by the major, sold by retailers, owned by consumers

One composition will usually generate various recordings (demos, final version, remixes, covers, lives etc.) while one recording is usually released on several media (single / album, K7 / CD / Vinyl / MP3 etc.).

Labels do not only get money from the media sale, they also own property rights on both the composition and the recording. Consequently, they are paid as soon as an external person or company uses one of its entities – the composition (author rights) or the recording (airplay revenue).

A media-less industry

How the hell is that related to 1800 years yet?! We are getting there. The key one needs to understand from that period is that we didn’t knew how to record a sound, let alone save that recording on a media. Only the composition existed.

In spite of this background of no recordings nor airplay, the very first sales charts of music started to appear at that time. Indeed, the very first sales charts, including initial Billboard publications (from 1900), were Top Sheet Music Sellers. The legend says White Christmas by Bing Crosby sold as much as 7 million copies on sheet music alone.

Today, we often debate if a viral video – remember Harlem Shake? – which airs an audio song should count among streaming points of the song only because the artist doesn’t appear on the visual side. Initially, the artist wasn’t even featured in the audio, since there was no audio media. Early Top Singles rankings were charts showing the most successful songs, independently from who was the singer. More often than not sales from all artists singing the said song were merged together.

1880s/1950s – Let the music play!

The first record player

In 1877, Thomas Edison came out to save us, poor humans waiting desperately a musical recording player. He invented the Phonograph. The orange cylinder you can see in the picture was the CD of its time, the first music media ever! Speaking about media, the very first player using disks as we knew was the Gramophone which was released in 1889.

We will benefit from this historical reminder to highlight one other forgotten key item that played a massive role in record sales over many years: the music player. Regardless of the era and the format, the number of effective music players in the market always limited the music industry. All crisis periods of the music industry have always been the consequence of a difficult transition from one format to another. Thus, from a music player to another.

Technical limits of cylinders were catastrophic, so were initial disks’ physical constraints. Early ones had a playing time of a mere 2 minutes and were broken after only a few plays. The music market at the time was consequently limited to songs only, the album concept wasn’t existing.

Records reach everyone’s home

Over 20 years after its release, in 1910, Gramophone eventually passed Phonograph in terms of sales, which highlights how much of a struggle transition of music players have ever been. By 1920, the Gramophone was largely dominant over its competitors. Record sales were already pretty healthy. The early 1900s saw hits pass the million mark. As amazing as it may seem today, during year 1921 the US record sales topped the 100 million units milestone.

A problem quickly emerged yet, the lack of norm. Back then, disks had no pre-defined size nor speed. To solve the issue, majors started to focus on the now iconic 78 RPM record. It became the standard of the industry in 1925.

The first popular singers

The main concern was to increase the length of the record that still hadn’t pass the 4 minutes limit. Despite this issue, Billboard published the first Top Album chart in March 1945. Again, the question coming out is how was it possible? The answer is rather easy: the first albums ever issued on the market were barely boxes containing a set of several singles.

In 1948, while 350 million singles were sold during the previous year in the US, the first proper album entered the market. This was the utterly cult LP (Long Playing), that some of us knew under the name of 33 1/3 RPM.

In parallel of technical evolutions, the recording brought a new actor to the industry: the singer. Majors started to hire several of them. Functions were still very segregated yet. The first actors were composers, the most famous of them being George Gershwin. Once the composer completed his work, the major used to send it to all singers under contract. Then they all recorded the new song. This is how during the 40s editions of the Billboard, the Top Singles was still independent from the artist. Various groups of musicians and artists recorded and released the same songs. Among all those voices, one stood out over all others: Frank Sinatra. No question why he got nicknamed The Voice.

From singles to albums

As we move over the years, we start noticing a very interesting point: the inherent relationship between the recording and the media. As the latter evolves, the former changes as well. Quite logically, Capitol, ancestor of Universal, adjusted their way of recording due to the strong emergence of the album format. In the US, the format grew from 1 million units sold in 1948 to 32 million in 1955. The musical concept of the album was created in 1955. It could have been done by no other than Frank Sinatra with the unique album Songs For Young Lovers. This was the very first time an album wasn’t a compilation of standalone songs. Instead, it was an overall concept with songs consistent with each other. Sinatra was still strictly a singer yet, he wasn’t involved in composition or lyrics.

We notice how the music industry lived for 78 years before the advent of the album. This fact is the perfect illustration of what came anew much later. Downloads completed the loop by setting back an industry massively axed towards singles.

1958/2001 – The modern day era

Singers-songwriters re-vamp the entire industry

With this new musical background, the Billboard magazine continued to cleverly adjust in 1958 by creating the Hot 100.

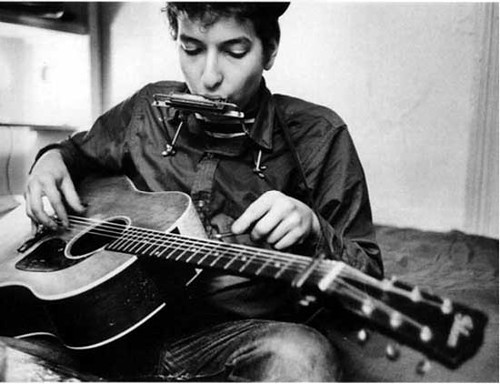

We previously saw how clear the distinction was between the singer, the author and the composer. One man will drastically change this situation: Bob Dylan. He brought to the light the concept of Singer-Songwriter in 1962.

An absolute revolution, suddenly we move from the singer to the artist. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones and various others quickly flooded the market by following Dylan‘s steps. Artists from the past generation like Elvis Presley end up being classified as Vocal Acts. Their artistic credibility suffers a huge backlash. From the Beatles‘ US explosion in 1964 until 1969, Elvis will manage to chart a mere 1 single out of 39 released inside the US Top 10. It competes against 32 Top 10 hits from 1955 to 1963.

We are all artists

The whole market benefited from this map-changing era with physical formats pacing at a solid level of sales. A total of 385 million albums were sold in the US during year 1973. The Singer-Songwriter concept created infinite possibilities. This opened the door to every single person to create music. Previously, it was something restricted to the few majors’ elite consultants. A large wave of new and diverse artists broke the main audience. From 1965 to 1975 the creativity of the music scene exploded with the likes Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, David Bowie, Michael Jackson, Jimi Hendrix, the Doors, Neil Young, Marvin Gaye, Deep Purple, ABBA, Stevie Wonder and many more hitting the shelves.

During that period, the Compact Cassette, first released in 1964, continuously grew. It reached the status of biggest format by 1984. After its early 70s explosion, the overall market stabilized. In fact, music styles started to be more diverse, and thus, less and less consensual. These styles revealed a more marked persona, a la Disco. Most of these genres haven’t got the universal appeal of past glories. With existing formats getting pretty old, the beginning of the 80s was a difficult period. For the first time since 30 years, the music market went down. In the US, from 540 million albums sold in 1978, it decreased to 420 million in 1982.

New marketing tools

Two detonators shortly stopped the crisis yet, both released in late 1982. The first savior, in the musical side, was the all-time bestselling album, Thriller by Michael Jackson. The second, in the technological side, was the arrival of the Compact Disc in Japan. Yes, there is no mistake: the CD appeared as early as in 1982. With the juggernaut success of 1978 soundtracks Saturday Night Fever and Grease, and now the one of Thriller, the industry got its lessons learned. The visual support was a significant marketing key to be added to radio plays.

It is time for a short side-note about promotion tools used by majors. Nowadays, rolling Tops like iTunes are updated every single minute. It completely destroyed the perception of an efficient promotion in the eyes of the public. Historically speaking a few TV shows had success-changing impacts, notably the Ed Sullivan Show from 1948. Nevertheless, the TV support has always been rather minor for musical promotion. Writing press first, followed by radio airplay, have always been the main channels of promotion and investment for majors. They were also the major factors for sales increases. Every claim we hear about an artist having “no promotion” because he hasn’t performed live is fundamentally wrong.

All artists, all, have promotion investments done proportionally to their selling capabilities. Often, fans of old glories feel their artist should be promoted more. They are missing that the appeal of their favorite act is not widespread enough anymore to justify larger investments. Maximizing sales is not the be-all and end-all of majors. They want to maximize benefits instead as the point is to be profitable. They would quickly run into bankruptcy if they were putting millions of dollars into acts with restricted impact!

The CD thriller

Ever increasing worldwide population, new economic boom, fresher physical format, explosion of MTV. Factors were numerous to put the music industry back on track. Brothers In Arms, by Dire Straits, became in 1986 the first album ever to top 1 million sales in CD format.

It took CDs six more years to become the biggest format yet. This happened in 1992, some nine years after its release. While looking like a slow and painful climb of almost a decade, this is actually the fastest rise to the top a physical format ever managed.

One more time, the music industry evolved as per media evolution. Due to the CD expansion, during early 90s, majors flooded the market with career-spanning Best of albums. All artists who sold large amounts of LPs got theirs. ABBA, Madonna, Elton John, Queen, Dire Straits to name a few. The latter is an interesting case. Naturally, the first major compilation aimed for LP replacement came from the favorite act of CD buyers. The title, Money For Nothing, was reflective of the beginning of a massive cash-in period for the industry.

This phenomenon of format replacement by the consumer is crucial. This is very precisely what was going to devastate sales from mid-2000s. It will also definitely kill the physical format by 2020.

With technically reliable physical formats, promotional plans fully mastered and massive financial revenues, majors used this period for geographical expansion. That’s why the 90s saw some albums, among which Titanic OST, Bodyguard (Whitney Houston) and Dangerous (Michael Jackson), break sales records in Asia. Some artists got insanely successful there like Mariah Carey.

In 1999, the music industry registered its all-time peak with a trade value of $25,2 billion. With huge countries yet to be explored, the future was looking incredibly promising…

Music industry – The digital years

2002/2005 – Deployment years

Years of contradiction

The digital era is the era of all paradoxes. The one which deleted the physical format while searching for the best one. Which saw all-time highs in terms of sales volume that go on par with some of the lowest years in terms of revenues. It’s also when the constant evolution of technology brought all processes related to media, revenues and promotion back to the very original form they had in the first years of the music industry.

This industry has always been concerned about adjusting to consumers’ habits. All physical formats got released before the need was felt by consumers. Plus, all formats which disappeared did so barely because a more modern one was available. In 2003, for the first time ever, the opposite situation happened. The collapse of a physical format forced majors to rely on a new one, digitals. It means the music industry felt short of anticipating upcoming changes, being a good 10 years late. This strategy error will end up being an awfully expensive mistake. In fact, IFPI reports tell us that trade value of the industry dropped from $25,2 billion in 1999 to $14,2 billion in 2014.

The iTunes Store: a worrying albeit promising new actor

In April 2003 in the US, in June 2004 in Europe, in December 2004 in Canada and in late 2005 in Japan and Australia. The iTunes Store was deployed all over the world from 2003 to 2005. Quickly, charts from most countries started to take into account digital sales. Expectations were high for this solution considering how many advantages digitals had for the consumer. There was no more changes in record format requiring to replace your old disks. It was possible to copy the song on various hard disks. To do backups, to listen to it on various computers and phones.

Indeed, the first corollary of the end of a physical format solution was actually the main revolution of the digital format: consumer finally got rid of the Music Player constraint. Once he purchased a download, he could listen to it anywhere he wants.

A second corollary to this formula was just as important. The number of potential consumers was instantly much higher. In brief, every person owning an internet connection was able to download. That represented way more people than consumers owning a proper music player.

2006/2012 – A continuous growth in sales

The inflection point

A mere three years after their introduction, in 2006, downloads already boosted annual US units to their all-time peak. Standards on the likes iTunes was a $1 price for a song and $10 for an album. This felt just wrong as a single was now 4 times cheaper than in the past while the album was still just as expensive. It decreased a lot the interest of the latter. Most big albums still only have 4 singles, cherry-picking them for $4 was much more logical than buying them as well as 4 to 5 fillers for $10. As a result, and as shown in the graph above, while sales kept increasing, revenues kept going down.

Thus, the entire industry was awaiting for the inflection point, when digital sales revenue increases would top physical sales revenue drops. In 2010, we thought that point was reached. Industry executives considered the crisis was soon going to be something from the past. Figures really looked that way from 2010 to 2013. In fact, worldwide overall revenue decreased a mere 2% in 3 years from $14,9 billion to $14,6 billion.

A world of specialization

During that period, we attended to the tsunami named Adele. The most striking fact in her success wasn’t its size since several albums from the past did just as well or better. Instead, it was how unique such a success was in the last 10 years. Since the 60s, almost each year had its pack of blockbusters, but that trend suddenly stopped in mid-00s. This absence of blockbusters wasn’t that much due to the overall decrease in sales. The main reason is how much fragmented the market got.

In each country, local industries have been developed and local artists are often favored by consumers. Tastes became more fragmented too. Additionally, the digital world and the ever-increasing number of specialized radios and TV channels enables fans of all genres to focus solely on their favorite sounds. This is why the 2005-2010 period saw many albums reach incredible sales here and there but not globally. There has been Nickelback in the US, Amy Winehouse in the UK, P!nk in Australia, etc. Globally though, none reached that A-league status in all markets worldwide, none until Adele‘s 21.

2002/2012 – A continuous drop in gross

No Money No Party

As an illustration of this situation, 21,911 albums were released in 2000 in the UK, this compares with 52,552 albums newly available in 2009. As for local releases investments, we can notice how much better they held than investments on international sellers. For example, in 2007 in France there was 14 international artists with a promotional investments exceeding 1 million euros. This included 2 artists with a promotion budget over 3 million euros. These numbers were down to 4 and 0 respectively in 2014. In the other side, 13 local acts had promotion budgets over 2 million in 2007 against 14 in 2014. As the crisis strikes, majors have less money available and react by restricting their investments to low-risk profile artists.

The hardest part for the artist is not to sell well. It is to prove that your universal appeal is big enough to justify large investments on your shoulders. As the music industry is not as profitable as it used to be, that “big enough” must be bigger than in the past. During the 90s, each main major had from 10 to 20 A-List artists that received huge promotions worldwide. Nowadays, each major only have 2 or 3 such artists. Even past glories a la Mariah Carey got their status downgraded, being now promoted in lower profile media in most countries.

Majors are under threat

As mentioned in the 19th century part, the music industry has three distinct parts – the composition, the recording and the media. Originally, there was no media at all. Labels were owning property rights on the composition and later on the recording. Obviously, when the media was created, they earned a lot of money selling it during more than 100 years. Therefore, they were pretty reluctant to move into the digital sales bandwagon. That’s why they were ten years late on this evolution. With it, they lost both profits from sales of physicals media and distribution earnings. Indeed, iTunes doesn’t belong to them.

Their whole legitimacy was questioned in this new environment. Independent artists got more and more numerous. Confirmed acts started to think about releasing themselves from majors constraints a la Radiohead. This band released in 2007 the cult album In Rainbows on their own. Another impact is the universality of artists decreasing even more, explaining once again why blockbusters hardly come out anymore. The whole irony of the Adele phenomenon is the fact she was the new universal artist the industry was looking for while she was signed by an independent label.

Even though all performance indicators were dark green in 2010 to believe the crisis end was close, it wasn’t. Majors’ worst nightmare got real. Not only their legitimacy is doubted, in 2013, after two years of stagnation, but digital sales started to freefall.

2013/2015 – The switch

Bye Bye Sales

In 2013, the best selling album of the year, Midnight Memories by One Direction, shipped 4,0 million copies worldwide. An apocalyptic result for a yearly bestseller, the lowest ever since IFPI started to publish them in 2001. For comparison purpose, that year of 2001, 25 albums sold more than this mark.

Drop in sales isn’t something new as it is running for over a decade. However, thanks to downloads, this drop wasn’t as big as it used it be in mid-2000s. From 2013 yet, as downloads themselves started to fall, sales as such were into a real black hole. In the US, the RIAA tells us downloads increased by 4% in 2013 Q1, reaching its inflection point. From that moment on, they never increased again. The year completed with a 3,1% decrease despite the good start. Songs downloads dropped a huge 12,5% in 2014 and again 12,5% in 2015. All around the world results have been pretty similar.

When the decrease of downloads started after almost ten years of continuous climb many though it was barely the result of a lack of big hits. The reality was way more cruel. The direful fall was true for both singles and albums, for both old and new releases. In 2014 various indicators reached lows unseen in 40 years. Acts as big as Madonna, Janet Jackson or U2 are failing to reach Gold status in many countries. These results would have been considered absolutely impossible a few years earlier.

Unlike past crises, there is no new format expected to take over falling download sales. The average consumer is not buying individual recordings anymore. Sales of both albums and singles are dead.

Bye Bye Sales.

Hello Subscriptions

After reviewing the music industry history, what strikes one the most is that it goes further than the simple model we know. The industry is more than an album or a single of an artist that the consumer buys. All schemas are possible. The album format, the physical record, the music player, the artist, the singer, the major. All these elements, as essential as they may seem, have all been left out of the music industry model at some point. There seems only two elements ever remained and ever will: the music and its purchase. But here again, we are wrong.

Every era had supposedly essential elements ignored, and the streaming era will get rid of a new one: the purchase. The business model structured around the purchase of a standalone music piece (sheet, song or album) is over. In the end, and incredibly naturally, the only element that appears to be really essential in the music industry is the music itself.

If we look around at additional industries, not being limited to music one, the Cloud is revolutionizing various methods. Companies understood that possession doesn’t need to be physical. It goes further as even digital products do not need to be stored locally. Why would we ask millions of people to download a song if everyone can listen to the same shared file?

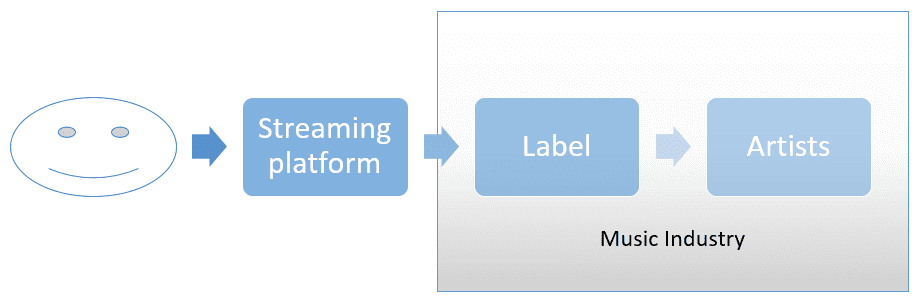

A new business model

Coming back to the composition / the recording / the media panorama, we realize the latter category will now be a shared media which won’t be purchased anymore. The consumer simply purchases the right to access this media. Is this model sustainable?

A key indicator on 2014 and 2015 reports, more important even than the drop of downloads, is the increase of streaming. Each one is worth about $0,006 for the music industry. Clearly, tons of streams are necessary to compensate revenues lost because of sales fall. In the US alone, 163,9 billion streams were registered in 2014, a gigantic of 54,5% boom. They exploded again in 2015 to 317 billion, an increase of 92,7%. While the IFPI has yet to publish the Digital Music Report related to year 2015, streaming helped digital sector (that encapsulates both downloads and streaming as well as a few performance rights) to continue growing. It means the revenue increase of streaming more than made up the fall of download sales. Digital market revenues worldwide per year:

- 2009: $4,4 billion

- 2010: $4,7 billion

- 2011: $5,3 billion

- 2012: $6,0 billion

- 2013: $6,4 billion

- 2014: $6,9 billion

A dizzying explosion

By the end of 2014, there was 41 million paying subscribers to streaming platforms, led by 15 million subscribers to Spotify. While there has been no official data issued at the end of 2015 so far, Spotify alone increased its subscribers to an estimated 25 million. Newly created Apple Music hit 10 million in six months only. The last Deezer count was on 6,3 million while Jay-Z‘s Tidal passed the million mark. Overall, the number of paying subscribers to streaming platform is likely around 70 million by now. The increase has been outstanding during last few years:

- 2010: 8 million

- 2011: 13 million

- 2012: 20 million

- 2013: 28 million

- 2014: 41 million

- 2015: estimated 70 million

One may wonder why the industry hasn’t jumped into streaming from the start rather than wasting time on downloads. The point is, offering 30 million songs, as Spotify does, implies immense fixed costs. Despite amazing results the Swedish giant had a cumulated loss of $400 million from its creation to the end of 2014. Strong marketing investments and expensive deployment plans in new countries are causing this situation. Expectations are still fairly good. The effectiveness of promotion is increasing and at some point deployment plans won’t be needed anymore. Furthermore, the amount of people turning down former sales system increases as well. Spotify or Deezer also had the handicap of starting from zero with no trademark. The 2015 arrival of industry monsters like Apple and YouTube will put streaming results into a new dimension.

Hello Subscriptions.

Music industry – The future

Downloads vs streaming, the war is open

The Future completes this trilogy by detailing how the music industry will be looking in upcoming years. How will each format evolve? How will the whole market perform? Which elements will be key in determining each of these points and why? To answer these questions let’s forecast how the music industry will be looking by 2020.

The digital world has changed our habits

Considering we all live in this current era, most of you already know the differences between downloads and streaming. Rather than repeating known elements, we will focus on studying what is implied by them and how they will impact upcoming years.

Before checking those differences, let’s analyze specificities brought by downloads. Historically, we have always been exposed to a restricted number of songs. As a result, it seemed quite normal to also buy a restricted number of records. Internet destroyed this reality, nowadays, we are exposed to a far greater number of songs from many more artists.

As levels of both discovery and awareness naturally increase, the average consumer has more knowledge than in the past. People never listened to as much music as during the digital era. This trend will accelerate in the future considering reports tell us 8-12 years old kids listen to over six hours of music per week, over twice as much as during the physicals era. This overall increase in knowledge and culture concluded into a unseen situation:. In the US, in 2015, for the first time ever, sales of catalog items, e.g. songs and albums over 18 months old, topped sales of new releases. This is true for albums but also for songs downloads as shown below thanks to this Soundscan data:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5926733/Screen_Shot_2016-01-22_at_4.05.17_PM.0.png)

… and raised our expectations

Therefore, consumers naturally expect a large set of songs to be accessible. They do not want anymore a few new releases only to represent their entire panel of choices. That’s the outrageous nonsense of downloads. It’s an open window to the entire music world that requires you to pay for each and every small piece you want to hear. Streaming solves this anomaly.

Another fundamental difference between both systems is that a downloads still require a physical device with the song available in local. It is dematerialized but a media is still mandatory. On your friend’s house, you can’t listen to your playlist unless you spent your precious time in copy and synchronization processes. On that same friend’s house, you barely need to open a web browser and log in. You will get all tracks you want and all your personal playlists.

To own or not to own

Which advantages downloads provide over streaming? There have been mostly two. The main one was that owning a song enables to listen to it without an internet connection. This is a key factor. In fact, moments favored to listen to music include travelling by car, moving in public transports or during vacations. Internet access isn’t a guarantee in these moments. This problem is mostly solved by paid subscriptions on streaming platform. Most of them provide the capability to download a fixed but large number of songs locally.

The second positive side of downloads is to pay only one time for a specific song. With streaming, no matter if you listen to music or not you will still pay your monthly fee. Yet, this is an issue in theory only. Mobile unlimited subscriptions and internet connections of smartphones proved that once the habit of using these services is taken consumers can’t get rid of it anymore.

Boundaries of streaming world

Admitting sales will keep collapsing, can streaming make up for this loss despite its constraints? Previously, we mentioned the music industry peaked at $25,2 billion in 1999. Streaming revenues reached a billion in 2013 and estimates are close to 3 billion for 2015. There is still a massive way to go.

Streaming mostly depends on internet connection and people mostly listen to music while moving. The junction of these two factors implies streaming evolution deeply depends on smartphone propagation.

Standard price for a streaming subscription is $10 per month for a user and $15 for a family of 6. That’s between $30 to $120 per user per year depending on your configuration, so let’s assume $75 per user. Streaming platforms reverse around 70% of the amount going to the music industry. A quick calculation tells us it would take 480 million paying subscribers to tie the all-time peak of 1999. At the same time, smartphone penetration is exploding. From under 10% of the population owning such a device in 2011, to over 30% by 2015 and more than 2 billion distinct users, the potential is huge. This still means 24% of smartphone owners would need to subscribe a streaming platform to tie 1999 results. A pretty optimistic scenario.

Additionally, the 600 million buyers of music in 1999 spent an average of $64. In the digital era, that amount decreased as average iTunes user was spending $48 a year. Independently of the period, spendings were always close to these two figures. Hence, how would we expect people to spend up to $120 a year on streaming? This system is twice as expensive as buying music used to be. That’s hard to digest, especially since downloads largely devaluated the perception of music worth.

2020, streaming in full force?

A service more valuable than ever

Physical formats disappearing, downloads crashing, streaming too limited to ever take over. It’s all truly depressing, isn’t it? Obviously, no, it’s not. Clearly, the current context doesn’t enable to live again the music industry’s hey-days, but how will be this context by 2020? [Edit : Want a market outlook as of April 2024? Head to our article about the streaming market in 2024 right here!]

As we noticed in previous paragraph, there is two key indicators to forecast upcoming years. The number of paying subscribers and the amount of money they are willing to pay.

Smartphone propagation is limiting the former but it is increasing incredibly well. By 2020, expectations for the number of smartphones in operation stand on near 6 billion. If we have a look at China, it’s a market where foreign acts almost never sold a thing. In fact, the biggest foreign albums of all-time there struggled to sell half a million copies. There is already over 800 million internet users. Paying subscribers to downloads services are up to 50 million. While the last IFPI report ranked China as the 19th largest market for music, the country will most likely rank at least inside the Top 5 by 2020, by that time the country will have over 700 million unique users of smartphones.

The latter indicator, e.g. the price consumers are willing to pay, is also favorable to streaming. In fact, despite $120 being almost twice the old $64 average of spendings, the service is not the same anymore. Instead of buying a few albums, an average streaming service user will listen to more than one thousand different songs per year. No more music player limitation also improves greatly the service, which ends up being naturally worthier. We can also stream all day long rather than playing a CD only at home after work. As for the old $64 average, it is made of two classes of consumers: regular buyers and casual buyers. The first group used to spend a huge $380 per year in music purchases. Basically, for them spending $120 for a better service is truly a given.

Upcoming changes of environment

Pending official numbers, streaming paying subscribers are estimated at over 70 million as of 2015. Below are some tips that will impact positively these number in the future:

- The number of smartphones in use will keep booming

- 3G/4G connections are booming as well

- The industry is barely starting to promote streaming platforms

- Industry catalogs are still not completely available on streaming platforms

- Sector giants like iTunes and YouTube just ended to jump into the bandwagon

- Quality-wise current streaming platforms can be easily improved

- Offline mode is not fully developed and awareness of it is low

At the very start of this article, I mentioned I initially wrote that journey in French in early 2014. At the time, I wrote about Apple and YouTube not operating in the streaming sector so far. They both did so one year later. The upcoming IFPI Digital Music Report 2016 will show how much of an effect they are having. I’ll be posting an appendix to this report once it drops.

Trade value of the music industry in upcoming years?

All factors mentioned above result into promising expectations. There have been 250 million iTunes buyers, with 50 to 100 million likely to purchase a subscription by 2020. That’s about at least five times the current count. Assuming the same increases for the full sector would mean 400 million subscribers. As Spotify keeps growing fast while new local Asian services will explode as well, this is a very realistic target. Additional revenues from ads supported streaming would generate the last billions needed to top the all-time 1999 record. Then, there will still remain some casual physicals purchases and performance rights for radio airplay. All in all, forecasts of a $25 billion industry isn’t out of reach.

A last point remains which is the good old formula Start cheap & Go Up. This well-known industry technique consists in providing a service relatively cheap, get users usage to turn into a habit, and then increase the price of the service. If we apply this principle to our case would set subscription prices to $15-20 in the future. This is without mentioning specific subscriptions which will necessarily appear in the future like an additional $2/3 for each family member, or $5 more to couple streaming service with a unlimited download functionality.

I’ll be taking a risky bet to conclude by saying a trade value of $40 billion within ten years is possible. There is only one thing to do if you want to make this expectation a reality – let the music play! Oh, wait, this is about streaming, that’s right, but what about other formats? How will they perform in the upcoming years?

My dear old CD – Le roi est mort, vive le roi!

Vinyls

Yeah, I know, I loved my CDs too. Just like many of you, I grew up with them. Today, they are massively ignored although being widely available. Tomorrow, they will be a niche market and people will start looking after them. This is the irony of human race.

Will the physical format truly disappear yet? The answer is no. For the average consumer, it won’t be there anymore. For collectors, the professional or the nostalgic, it will forever be a nice sweet. As a proof of that, below are yearly Soundscan sales in the US for Vinyl format, which registered post-1991 yearly record every year since 2008 included.

- 2000 – 1,500,000 – old record in Soundscan era (from 1991)

- 2006 – under 1,000,000

- 2008 – 1,880,000

- 2009 – 2,500,000

- 2010 – 2,800,000

- 2011 – 3,900,000

- 2012 – 4,600,000

- 2013 – 6,100,000

- 2014 – 9,200,000

- 2015 – 11,900,000

The interesting point is how vinyl started to take off as downloads arrived. It became the elitist buying for people who though digital music was too cheap to be paid for. The vinyl boom was mostly due to rock fans, representing more than 70% of sales. As per the RIAA, in 2015, an unbelievable 18% of physical rock purchases were vinyl records. But the new interesting point is that vinyl sales of Pop records exploded 163% this year. They now represent 5,7% of all physical sales of Pop music, against barely 2,8% last year. It reveals how this elitist buying of vinyl is extending to all music fans.

CDs

The only question remaining is which format will survive – the vinyl, that may keep booming every year, or the CD, that once lower will start itself to get back some reward. One may think favored format will be the CD because it relates to more current buyers and because its quality is higher.

The main reason of buying these physical records is not the music itself. In fact, while vinyl sales explode, sales of turntables struggled during various years before finally taking off in 2014. The reason is known: over half of vinyl consumers never listen to them. Their primary functionality is for decoration purpose. They are an easy show off of some cultural knowledge. The general public believes owners of vinyl are cool intellectuals. Owners of CDs are late and ripped off. Hype trends tend to not last and these caricatured images may evolve. Nevertheless, considering the phenomenon has been going on for a decade now I’ll still place my bet on vinyl as the physical record survivor. One thing is sure, large international releases will still get CD and Vinyl releases for many more years.

Downloads

What about downloads, how will they perform by 2020 ? Pretty badly. They will be gone for good. Let’s be real: nobody care about owning a digital file. Now that streaming platforms enable to store songs locally, there is absolutely no reason for downloads to survive. The brutality of download sales drops faced since Apple started its streaming service sustain this destiny. In fact, they are now dropping about 25% versus one year ago.

Radios

With a catalog of 30 million songs available 24/7 on streaming platforms, we can question the relevance of radios. We have to keep in mind that in a streaming model, we still have to select what we want to listen. The radio segment is precisely that one: selecting something to listen for us, enabling people to discover new acts. Obviously, the playlists system available on streaming platforms fulfil this role but not completely. They are not as well-known as radios. Also, specialized stations don’t interest casual listeners.

The main channel for listening to music among teens is YouTube, used by 64% of them. Still, radio remain way ahead as the best place for discovering. More precisely, 48% of the times we hear a song for the first time, we do so in radio. Remaining forms of discovery are much lower as only 10% of them come from a friend’s advice and a mere 7% are done thanks to YouTube.

The number of ways to listen to music is so big it seems obvious that radio audiences is going down. Facts show that airplay has never been so high, breaking records every year. Nowadays, almost 70% of Americans listen to radio every day. Over 243 million per week. Even more impressive, adults spend an average 20% more time listening to radio than being on internet! How can we explain it giving the current fierce competition? Simply because the cake is bigger as we listen more music now than in the past.

Even so, like TV channels do, general radios will start losing ground in favor to more specialized stations to better fit with consumer’s profile. Although we like hearing new songs, we still expect them to be consistent with our favorite genres.

Streaming alternatives? Paranoid Android

By covering all eras we noticed how every format ended up dying after shining brightly. Will streaming suffer the same fate?

Many people though dropping sales were due to illegal downloading. The real reason was actually the same as in every other era: sales dropped because the related music player disappeared.

At cassettes arrival, turntables sales went down as they were more expensive than cassette players. Time for the population to switch record players, sales of cassettes sales topped sales of vinyls. From mid-80s, the public started to move on CD players, downgrading the interest in cassette players. They still survived until late in the 90s because of these players equipping old cars.

When cars moved to CD players, sales of cassettes completely disappeared. Then, the personal computer got into everyone’s house and CD sales boomed when these computers started to include CD players. At the same point, the Hi-Fi stereo got irrelevant, which pushed sales down in the mid-run.

Not only Hi-Fi systems disappeared, in early 2010s so did CD players from computers. The likes Notebooks, Ultrabooks, etc, do not have CD slots anymore. Vehicles too moved from CD to MP3 players. While most people had their eyes on illegal downloads, few noted the CD music players were dying. Ultimately, it was only a matter of time before the CD album would die as well.

The definitive solution

Whatever happens, we have to deal with digital music. Since it doesn’t depend on a player, nothing will require it to change. Currently, you can select either downloads or streaming, but as we saw, there is no match between both models.

Streaming is the definitive answer to the music industry. We can listen to everything, everywhere, at every moment. Just like it seems unacceptable to pay for each and every phone call or text, same will be true for music. The public want an unlimited subscription. Welcome to Spotify, Apple Music, Deezer, Google Play, YouTube Music and others!

More than ever, feel free to comment and / or ask a question.

Sources: IFPI, RIAA, Billboard, Nielsen Soundscan, Spotify, Forces, Common Sense Media, Zobbel, Telegraph, Music Business Worldwide.

2018 update – We are living the streaming era

Everything in its right place

Nearly 5 years after I first drafted this article, many things have changed. Back then, I introduced it that way:

Since my return (to charts & sales sites), I have got the chance to read a lot of topics and to observe as many elements misunderstood from the current state of the music industry. The largest part of figures published on charts sites don’t make sense anymore in 2014. We will try to change that!

My concern was that people were commenting on how many artists were “flopping”, because their pure sales were going down. Nobody cared about streaming. It was increasing fast already, but the general consensus was that it wasn’t a valid media. In a way similar to YouTube views, audio streams were disregarded. There was no awareness of the relation between drop in pure sales and increases in subscriptions.

Since then, the jigsaw extensively evolved because of streaming. Most charts and certifications changed their rules. The general public now understands and values it properly. The format is profitable for the music industry. It is changing the global map of revenues. Artists adjusted their releases.

There is still many unclear areas though. How much do premium users really pay? How much of it goes to the music industry? Which countries still ignore streaming? Will China become the #1 market in the world? Why do urban and Latin acts perform so well there?

Charts & certifications

If the consideration of streaming was low in 2013, it’s because the biggest charts in the world were still ignoring them. Back in February of that year, Harlem Shake by Baauer shot to #1 of the US Hot 100. It was made possible by a last-minute change of rules which factored in YouTube views for the first time. This was the worst way to introduce streaming. YouTube was there for many years, so it felt unfair. Plus, adding it just because a song was viral there looked opportunistic. Fact is, even if the timing wasn’t perfect, introducing streaming was inevitable.

The whole globe adjusts in time

A few years later, nobody doubt it anymore. In the US, the UK, Germany, France, Australia, Canada, Italy, Brazil, Mexico, etc, all countries started to include streams. The model implemented by Scandinavian countries a few years earlier appeared to be viable.

It was a progressive process, with 5 main steps to be made:

- setting up streaming-specific charts

- introducing streaming into official singles charts

- weighting streaming into official singles certifications

- introducing streaming into official albums charts

- weighting streaming into official albums certifications

This first run of adjustments has been done almost everywhere as of May 2018. As usual, Japan remains the last big market to separate formats, both in charts and certifications. For how long? We don’t know, after all they introduced downloads charts in late 2016 only.

The lack of norms

Ironically, 100 years after issues related to records lacking standard norms, we are back to the same situation. It’s better now since this flaw doesn’t impact the end user. Still, organizations managing charts and / or certifications of all countries raised their own rules. There have been no consistent adjustments between them.

It must be said that while certifications bodies are affiliated to the IFPI, they have no relation between each other. Also, the same set of rules may not make as much sense in all markets. For example, the share of YouTube is much bigger in Latin America. It’s not possible to ignore it there, while it is in Germany or in some Asian areas.

For chart freaks, it’s a real nightmare. The lack of norm creates a lot of room of errors when gauging sales of artists. Labels report certifications from various countries for marketing purpose, but it is all very misleading since they all fit to distinct rules and conversion ratios. The only official document where global streams and sales are combined with a consistent rule is inside the Annual IFPI Report. We can only hope for actors like the IFPI, the RIAA and the BPI to align their standards. Ultimately, adding complexity can’t be a positive move.

Remaining debates

While we can discuss about the ratio to apply between streams and sales, between songs and albums, they are only details. The fundamental debates around streaming involves video streams and freemium streams instead.

After applying the first 5 main steps to incorporate streaming into charts and certifications, official bodies are now at the stage of adjusting flaws. In Germany and Austria for example, only premium streams are counted for charts and certifications purposes. The SNEP from France announced the same measure last month. The BPI from the UK is considering the same rule too. It’s a sign of the times as freemium accounts are losing ground. They represented close to 70% of streaming users 5 years ago against 35% by the end of 2017. Spotify, where are registered nearly all freemium users, also reported their premium users stream more content hours than ad-supported users.

Then there is YouTube. It looks like most industry actors are pending evolution about the value gap to react. The value gap is the name given by the IFPI to the huge difference in revenue per user brought by YouTube in comparison to audio streaming platforms. To make it short, YouTube pays about 30 times less money per stream to the music industry. For that reason, these streams are still mostly ignored on global charts, even if they are accounted for in most of the American continent. We will have to wait and see what happens, but everyone is hoping for a legislation to fix situation.

Money, get back

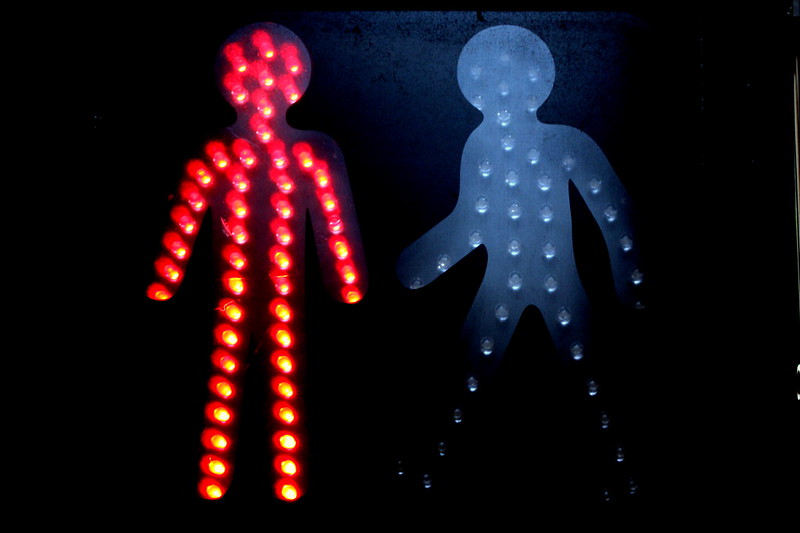

There have been a lot of controversy about the money generated by streaming. Guess what? All exact figures are available. Before getting into figures, we need to point out the money flow of the streaming business. A simplified model is displayed below.

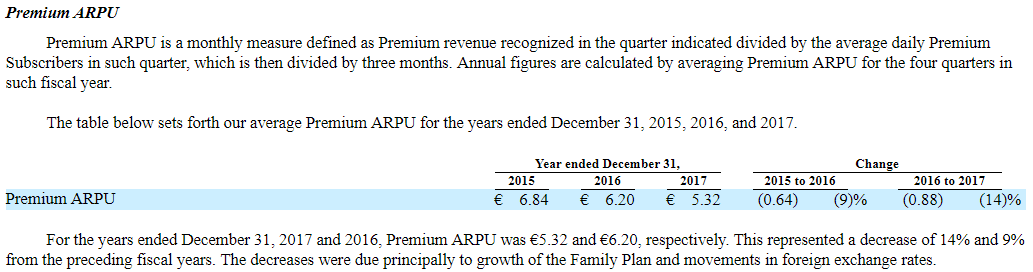

As you can see, the money goes into the music industry from payments of streaming platforms. Thanks to the IFPI GMR, we know they paid $5,569 million in 2017. With 272 million users, that’s $20,47 per user per year. Platforms always communicate that they pay more than 70% to rights holders. Considering users pay $10 per month, $120 per year, we can be surprised by this $20,47 average.

Content Costs

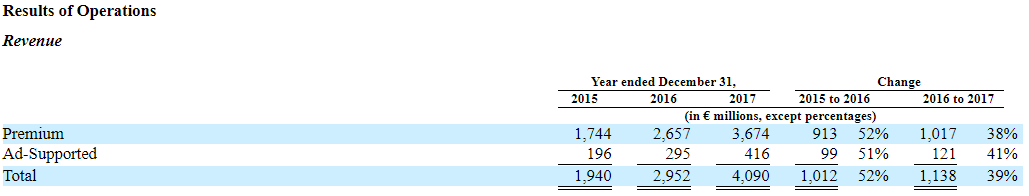

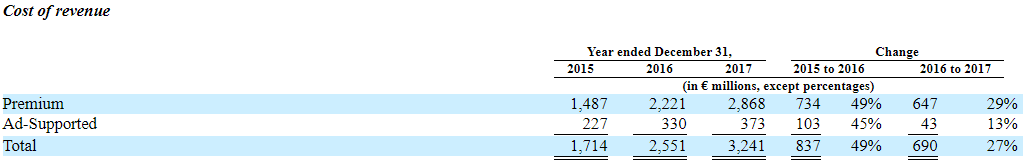

The fascinating and highly detailed financial report of Spotify for 2017 brings us all answers. Below is the amount of money they perceived from their users and thanks to ads.

The content cost or cost of revenue is the money paid by streaming platforms to the music industry. Results of Spotify are displayed below:

To sum up, they paid $3,24 billion to rights holders out of $4,09 billion. In other words, they reversed 78% of their revenues to the music industry. In 2015 and 2016, the share was 85% and 84%, respectively. As stated by the report, the decrease in cost of revenue as a percentage of Premium revenue was driven largely by a reduction in content costs pursuant to new licensing agreements. The strength of Spotify enabled them to negotiate better shares to sustain their activities. These ratios are similar for all platforms.

With a content cost of 78%, we would expect about $94 per user to reach the music industry. So, where does the money of the user disappears to go from $120 to $20,47?

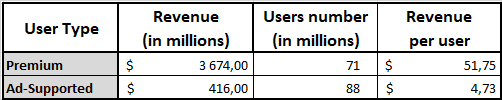

Number of streaming users

The number of 272 million users of streaming platforms is misleading. It includes 96 million ad-supported users. As many as 88 million are from Spotify. Below is the number of money received by Spotify per user.

Ad-supported users are nearly 11 times less profitable than premium users. Basically, the 96 cross-platforms freemium users are worth a rounded 9 million paid-for users. Thus, 176 (paid-for) + 96 (ad-supported) users equal to roughly 185 million premium accounts. With a $5,569 gross for the music industry, we reach a payback of $30,10 per premium users.

Time frame of subscription

Streaming is booming so fast that some numbers are completely different between the start and the end of the year. There was 176 million premium users by the end of 2017, but only 112 million at the start of it. Consequently, 64 million persons subscribed during the year. On average, they paid for about 2 months only though. Why so?

Most people join during the bi-annual trial campaigns from the summer and the holiday season. Persons registering in July only start paying from October. Persons registering in December will only pay from March of the next year. Then, we have ongoing trials from last year’s Christmas season. Also, the churn rate is at 5%. As a result, there is even more people who didn’t got their subscription for the entire year.

We are left with 64 million persons paying during 2 months. They equal to under 11 million premium users for a full year. In short:

- 112 million full-year premium users

- 64 million new premium users worth 11 million full-year premium users

- 96 million ad-supported users worth 9 million full-year premium users

= 132 million full-year premium users

We apply our calculation based on $5,569 million revenue once again to conclude on $42,2 per full-year premium users for the music industry.

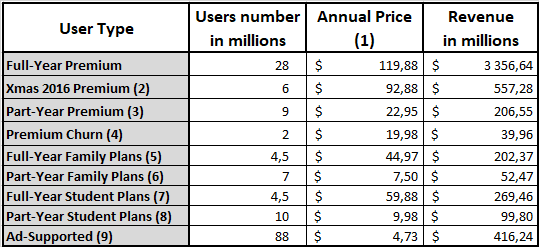

Family & Student plans

The price of $10 is true for US stand-alone premium users. Since 2 years, family and student plans are increasing strongly. For Spotify, Family Plans alone accounted for 22% of new users in 2016 and 31% in 2017. That’s 11,5 million subscribers who pay from $2,50 (for families of 6) to $7,50 (for couples). While there is no data about student plans, demographics of Spotify report tell us 33% of their users are aged 18-24. Obviously, their share is possibly lower among premium users. Still, we can expect student plans to account for 20% of all premium users. They cost to users only 50% of standard premium accounts.

How much we do really pay

Below table summarizes all elements together for Spotify users.

(1) Annual Price using US base

(2) Users from 2016 Xmas paid 3 months at $0,99 and then 9 months full

(3) Assuming they paid on average 3 months at $0,99 and 2 months full

(4) Assuming they paid on average 2 months

(5) Assuming 4 persons on average are plugged into each family plan

(6) Assumptions (3) and (5) merged together

(7) Actual data from Spotify report

We can notice the total of revenue from premium users add for $4,785 million. We know Spotify received $3,674 million from them instead. It means the various local currency prices and all special offers packaging Spotify with other services drop revenues per user by about 30% more.

Platforms key indicator is the number of users, not revenue

Why am I flooding you with all these numbers? To raise awareness on a key issue: the main concern of streaming platforms is to increase their number of users. They do appear on their report as the first key performance indicator. All offers of Spotify lately largely downgraded the revenue per premium user they are receiving :

The group has good reasons to prioritize the number of users rather than the ARPU. Thanks to large volumes they can then negotiate better rates with rights owners. It’s also the most efficient metric for marketing purpose. When going public, it reassures investors. More than anything, it creates the habit of using the service among consumers. One they subscribed, it’s a highway to make money.

In fact, many trials and student plans may become full-priced users afterwards. Impressively, if Spotify doesn’t gain a single user during 2018, they will still improve their revenue by about 35%. It only takes current users who registered during 2017 to pay for all 12 months in 2018.

The new global map

If there is one thing that never changed before streaming is the distribution of markets. The music industry remained dominated by English-speaking countries and then developed markets. Basically, the music industry got most of its revenues from North America, Europe and Japan. Streaming will completely changing this situation.

China to challenge the US?

Now that’s the big question. China has always been a non-factor of the music industry. Their market is filled with piracy since decades. Internet connections and smartphones revolutionized their background though. Streaming is now bringing more and more revenues every year.

The increase of the market has been insane. From 21st market in the world in 2013, it increased to 19 to 14 to 12 to 10. It went from being behind Denmark to seriously challenge Brazil which is itself exploding. Gross-wise, that’s a jump from $82,6 million to $273 million in 5 years. There is no slowing down as China improved by more than 35% in 2017.

Considering how populated the country is and how many people use smartphones, we can really wonder if China can challenge the US in the long run. That may seem ludicrous nowadays, but there is undoubtedly indicator going that way.

The example of the movie industry

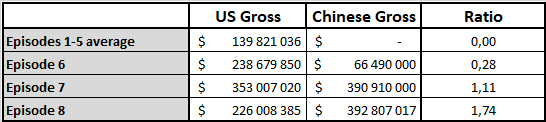

The movies industry saw the same revolution from China lately. It isn’t limited to local production as foreign movies are doing incredibly well. Below is a comparison of the Fast and Furious franchise in the US / China. All figures from Box Office Mojo.

Up to 2011, even international blockbusters weren’t released in China, just like main CDs. The episode 6 of Fast and Furious from 2013 registered 28% as much money in China than in the US. In 2015, the movie’s first market was already China. In 2017, the 8th episode performed 74% better there than in its homeland.

What seemed to be an exception is becoming the rule. Movies like Pacific Rim Uprising and Ready Player One also outgrossed the US total in China. In fact, it’s not a few movies which did better, in the first quarter of 2018 it’s the entire country that led the global market.

In music, the gap remains immense, the US market is ahead by 20 to 1. Don’t rule out China though. What’s safe to say if that if this latter country joins the very top global markets, it would be an incredibly positive news for the music industry.

The new market distribution

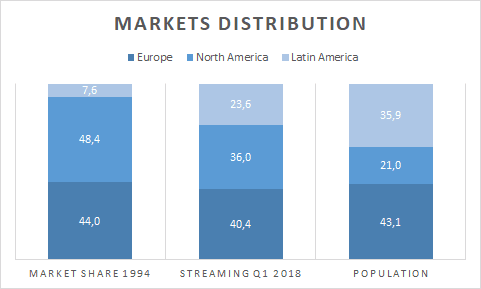

To highlight how much streaming is changing the balance of power of the music industry, below is an interesting graphic. It puts in base 100 the share of main regions in 1994, in dollar revenue, the distribution of Spotify users during the first quarter of 2018 and the current population of each region. The graphic focuses on Europe, North and Latin America since Asian markets use local software instead.

Back in 1994, North America represented more than 48% of the gross from these combined regions, Europe 44%. Latin America was down to a mere 7,5% in spite of its large population. Streaming reflects much better inhabitants of each region. Latin America represents a huge 23,6% of streaming users from these regions. As much as 21% of global users.

Apart from being fairer, the important meaning of this data is that music is more accessible to people with lower income. This is fundamental. Indeed, it impacts the repartition of users across the world, but also inside each market.

Lower income population best represented

During decades, we ignored that purchasing music wasn’t cheap. To buy a mere 1 album per month, possibly over $150 per year was needed. An Hi-Fi Stereo was awfully expensive. Lower income households had less money than others to buy music.

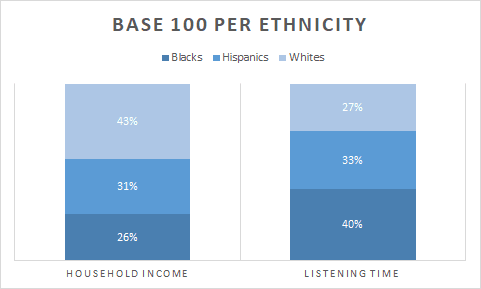

In the US, this context downgraded a lot the influence of black and Hispanic communities to the music industry. The country is home for 60 million Hispanics, 40 million black / African Americans and 20 million Asians among its population of 320 million. Their income is very different though. In 2016, Asians household income was as high as $81,431, Caucasians won an average of $65,041, Hispanics $47,675 and Black people $39,490.

Music has a relatively low impact on Chinese culture, which is the first origin of Asian Americans. For Hispanics and African Americans though the music is of massive influence. In a sales environment, their share of the market was much lower than their share in population. Streaming reversed the situation as shown by this report.

[Listening to music] among all teens, blacks average 2:27 and Hispanics average 2:04 per day listening, compared with 1:44 among whites.

For tweens (8-12), the situation is the same. Black tweens listen to music 1:17 hours per day, Hispanics 1:00 and whites 44 minutes. If we compare household incomes with listening times per ethnicity the result is striking:

Basically, white Americans play much more console video and computer video games while black Americans spend more time watching TV and listening to music. They barely adjust their entertainment media to their income. Music appears to be a very affordable entertainment.

Thus, it’s natural to see at last the music industry value much more communities with a lower income. Communities which do give more importance to music. The edge translating from white Americans to black Americans is obvious while looking at charts. Exactly 6 years ago, at the peak of downloads, the Hot 100 was led by Gotye, Maroon 5, Fun. and Carly Rae Jepsen. Today, the Hot 100‘s Top 4 is dominated by Childish Gambino‘s This Is America followed by a pair of Drake songs and then Post Malone featuring Ty Dolla $ign. No doubt, latin acts have also boomed since the transition to streaming has been done.

This example from the US is true everywhere. It is also valid for all minor ethnicities. Urban acts have been dominating streaming platforms of all markets. What would it take to see the balance evolve again? It will only take time. As years pass, gaps between distinct ethnicities get weakened. Black people will end up earning more too. Afterwards, all subsequent metrics will organically adjust too.

Sources: IFPI, Spotify, Billboard, Common Sense Media, Statista, Businesswire, Zobbel, Variety, Box Office Mojo.